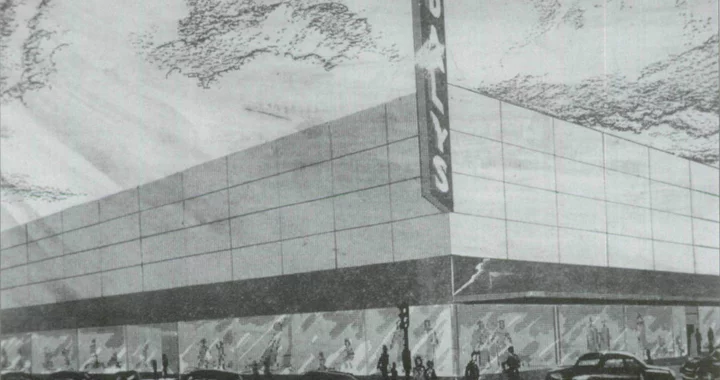

An architect’s rendering of the remodel of Daly’s Fourth and F storefront. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

A sense of loss overwhelmed me when I

learned that Daly’s Department Store was closing

its doors after 100 years. For some reason, I have

always felt that I could dash in there and do a little

shopping on my trips back home to Humboldt

County. Eureka’s own department store with its huge

plate glass display windows has played an important part in my life and in the lives of many others. It

is sad to think of it being gone. I suspect it is another victim of the shopping malls.

My first memory of Daly’s Department Store is a shopping

trip with my mother and younger sister. I must have been about

eight years old and was still a little uncertain which department store was which — J.C. Penney or Daly’s. But this was

definitely Daly’s — right across F Street from the Montgomery

Ward store and the two big dime stores — Kress and

Woolworth’s. Toward Fifth Street on the Daly’s side of the

street were Matthew’s Music House, the Bon Boniere, and

Arthur Johnson’s Menswear.

In the 1930s, a trip “downtown” was a rare occasion. We

wore our best clothes and took along our best manners. It was

a time when ladies always wore a nice dress and coat, silk

stockings, dress shoes, and a hat and gloves. We entered the

big double plate-glass doors on F Street and were dazzled by

the gleaming glass display cases of the Center Aisle. These

cases held gorgeous costume jewelry and fabulous perfumes

and makeup. To our right were the Hosiery and Shoe Departments, and behind the Shoe Department was the Girl’s Department with racks of beautiful dresses, sweaters and skirts.

I vaguely remember tiny dressing rooms at each corner of this

department.

Mother usually made our clothes, but this time she decided

to buy ready-made dresses for us. My little sister’s dress was

a high-waisted, puffed-sleeved dress with a full circle skirt

that whirled out beautifully when she spun around in circles.

The hem was trimmed with two rows of braid, and the fabric

was a cotton print of tiny flowers. She loved this dress so

much, she saved it, even after the skirt fabric was faded and

worn and split across the front from many washings and

wearings. It probably cost around $3.98 plus tax.

I shall never forget the dress I got that day. It was a lovely

shade of powder blue with just a hint of turquoise. The skirt

was separate from the top and had pleats all the way around.

The top was a short-sleeved jacket with big buttons marching

down the front. It cost $4.98 plus three percent California State

sales tax. This was a great deal of money at that time to spend

on a child’s dress which might be outgrown in a month or a

year. I wore that dress every chance I had. I wore it to shreds.

My mother undoubtedly got her money’s worth from these

purchases.

When we finished shopping, we went across the street to

one of the dime stores where we were each allowed to choose

10 cents worth of candy at one of the candy counters with big

covered glass displays of all kinds of confections-gum drops,

lemon drops, round chocolates covered with white sprinkles

called dragées, rocky road, licorice, chocolate stars, horehound

drops, red and white striped peppermints, pastel pink, white

and green tea mints-a veritable treasure-trove of goodies to

pick from. I always chose chocolate stars.

On other shopping trips downtown, we went directly to the

Yardage Department at Daly’s. On these trips, we turned to

the left of the glittering Center Aisle, and walked past the Ladies Glove Department to Patterns and Yardage. Beyond the

tables of fabrics, near the back of the store, were the Bedding

and Linen and Houseware Departments.

I loved to look at all the fabrics and smell their newness. I

imagined what I would make from each one. Sometimes

Mother would let me choose a quarter of a yard of this or a

quarter of a yard of that to sew new clothes for my Shirley

Temple doll. I learned to use my mother’s sewing machine

when I was seven years old by turning the wheel by hand. She

would not let me use the electric control for fear I might sew

my fingers! At that time, I longed to be a fashion designer and

make beautiful clothing.

Buyers traveled regularly to New York. This trip took place in the 1940s.

As a child, I never dreamed that I might one day work in

this store with all its wonderful merchandise.

I don’t think I ever explored the departments on the second

floor until I was in high school. These departments were

reached by the wide staircase or the elevator at the rear of the

store, leading directly from the Center Aisle. There was a

Beauty Salon, too, tucked away on the landing where the staircase turned to go up to Ladies Dresses, Coats, Hats, Sportswear, and Lingerie. The office and employee’s lunch room

and coat room were up there, too. The Men’s and Boy’s Departments were reached by a short ramp between the wrapping desk and the elevator. It was on another level, due to the

slope of Fourth Street at that point.

Once in a while as teens, my sisters and I were allowed to

ride the city bus down J Street to Fifth and F streets to do our

own shopping. Bus fare was five cents. Mother had a charge

account at Daly’s, and on special occasions we were allowed

to charge something “on approval”-meaning that we could

take it back if our mother didn’t approve of our purchase. In

those days, Daly’s had a delivery service and would send things

out to your house, so shoppers didn’t have to carry a lot of

packages around. Both hands were freed to do more shopping!

My older sister went to work in the office right out of junior college, and continued until after her marriage and the birth

of her first son. She must have been instrumental in getting

me a job there one Christmas season at the wrapping desk that

was tucked under the stairs. This must have been the Christmas of 1944, as I had just turned 17. My father died that Christmas, and my sisters and I felt we needed to help our mother as

much as possible.

The other wrapping desk girls and I worked at a long table,

wrapping gifts with double sheets of white tissue paper and

spools of ribbed ribbon in a rainbow of colors. We wrapped

double rows of ribbon in square or diagonal patterns, and

topped them off with curly poodle dog bows made of long

lengths of the ribbon that were curled with the sharp edge of a

scissors.

One day when the Christmas season was over, I showed up

for work, not knowing I wasn’t supposed to be there. I had

punched in on the time clock as usual. Charlie Daly came

down to the wrapping desk from his office on the second floor

and fixed me with a stem look. He usually cleared his throat

before speaking to any of the people who worked there, and

this time was no exception. I’m not sure who felt worse in this

situation, he or I, especially when years later I found out he

had gone to Eureka High School with my mother!

“Hammph,” he said. “Didn’t your sister tell you not to come

in to work today?”

DIDN’T MY SISTER WHAT? screamed my thoughts inside my head!

“N-no, she didn’t,” I managed to stammer, twisting my

clammy hands together and staring at the polished toes of his

shoes, not knowing what to do. Sometimes it is truly painful

to be young and unworldly. My sister might have forgotten to

tell me, or she might have felt she couldn’t tell me such an

awful thing.

The happy outcome of this was that Tillie Atwell, the office manager, took me under

her wing, tested my change-making ability, and put me

to work on the “tubes” — an

invention designed to speed

up service, eliminate theft,

and drive cashiers crazy.

Pneumatic tubes serpentined to and from all the departments in the store, ending in the office where they

opened onto a chute into two

troughs on a long wooden

table. There was room for

four cashiers — two on each

side. Our metal tills were designed to fit securely in a

second row of troughs, one

on each side of the tube

troughs.

Each cashier started with

fifty dollars in change in a

till that was made up ahead

of time, and locked and

stored in the safe until a

cashier needed it. When she received her till, she unlocked it,

and it was her responsibility to count that till before she started

using it and to balance it at the end of the day. When she went

to lunch, or left her till for any reason, she locked it and kept

the key. If it was short by more than a few cents, I think the

shortage came out of her pay. We always balanced within a

few cents. By that time the minimum wage was 50 cents an

hour.

The store opened at 10 a.m., but employees were there by

9:45. We closed at 5:30, with an hour for lunch and two fifteen minute breaks according to the law — one in the morning

and one in the afternoon. Lunches were in three shifts-the

first at 11 a.m. — too early, in my estimation. As the extra help, I

nearly always had to take that time. Then the whole afternoon dragged interminably. Each day, one of the cashiers had to

stay on to take late sales and answer the switchboard while

the others balanced their money and ran a tape of their sales

slips. The late cashier then had to stay later to balance out.

Our pay was given to us in cash in small manila pay envelopes with little pay slips attached to them. When I went back

to school at Humboldt State and could only work Saturdays,

my pay for one day’s work was about $3.60, after taxes.

As sales were made throughout the store, the clerks would

fill out sales slips, adding the 3 percent California State sales

tax that was already figured out for them on a chart in each

sales book. They made a note at the top of the sales slip of the

amount of money paid, folded the slip and its carbon copy

with the money into a cannister about eight inches long and

three inches in diameter, and sent it on its way through the

pneumatic system to us-the cashiers.

Once it reached the office, it announced its arrival by banging loudly as it spewed out the vacuum system, slid down the

incline and landed in front of us. Whoever was closest or quickest grabbed it, twisted it open, and spilled the contents onto

the narrow work space in front of the tills. We counted the

money, checking to see if it agreed with the amount the clerk

had filled in. If it didn’t agree, we phoned the clerk and returned the cannister intact for him or her to correct. Then when

it came back, we made the change, kept the original sales slip

for our till, and folded the carbon copy with the change back

into the little cylinder and returned it to the department.

The return vacuum tubes were in a double row of six, between and a little above us — 12 in all, numbered for each department. The cannisters had the department numbers on them

too.

An additional tube had been added at the outside end of the

rack of tubes, after the original system was installed. It was

number thirteen-Boys’ Department-and was a little hard to

reach if you happened to be on the switchboard, or sitting across

from the switchboard that day. Number thirteen always made

a high-pitched whistling noise whenever it was in use. We

always knew when we were dealing with the Boys’ Department, long before the cannister arrived.

Once in a while we would receive a fifty-dollar bill, on

more rare occasions, a one hundred-dollar bill. The average

sales per till per day were about six or seven hundred dollars.

During a Christmas season, I can remember taking in a little

over one thousand dollars on very busy days. One time, someone was passing counterfeit twenty-dollar bills. We all got a

lesson on how to identify them, and the whole office was in a

turmoil for several days.

Cashiers also ran the switchboard, a quaint relic of the Victorian Age, or so it seems now in these electronic times. Then

we thought it was a state-of-the-art system, and we all liked to

work on the switchboard. But you must remember this was in

the days of one telephone to a household, if people were lucky

enough to have a telephone, and two or four party lines on

many of those.

All the telephones in the store were routed through this

board. Small metal-lined holes connected to wires inside the

board. Two little lights, one red and one white were under

each hole. The names of the departments and the people in the

store with private telephones were fastened under their proper

holes. These were Office Manager Tillie Atwell and Credit

Manager Gladys Meline, among other telephones in the main

office, and the Dalys —John S., Jack F., Cornelius D. and

Charles.

There were four or five outside lines on the switchboard,

and as the lights came on indicating an incoming call, the

switchboard operator would plug a fabric-covered snake-like

line into that hole, open the “key” and say in a sweet, musical

voice,

“Good morning (or afternoon), Daly Brothers.”

Then she would bring up the corresponding cord and plug

it into the department requested, close the key, and ring the

phone. If she was not careful, she might push the key the wrong

way, and ring in somebody’s ear — a no-no!

Some sales were not cash sales. Many people had charge

accounts. When a charge sale came winging to us in one of

the little cannisters, we had to call out the customer’s name

loud and clear to Gladys Meline, the credit manager, whose

desk was adjacent to the tube system. She would then okay it,

or not. Other people in the office were qualified to okay charges

if she was out or busy with a customer. Sometimes she would

have to talk to customers on the telephone first, requesting

that they please come to the office and pay a little on their

bills before charging any more. Then she would okay a charge.

Gladys had a very difficult job and did it perfectly. Not

only was she responsible for all the charge accounts at the

store and for treating the customers tactfully and carefully,

she had to keep four giddy young girls in line on the tubes.

Not an easy task.

When things were slow, we liked to talk to pass the time.

This was forbidden. It was not business-like. If we had no

change to make, we must busy ourselves with making sure all

our charge slips were filed in alphabetical order. At billing

time, we were put to work stuffing envelopes with statements

and fliers for perfume or lingerie. Then, if we STILL had nothing to do, we had to go through stacks of old cash sales slips

to make sure a charge slip had not been accidentally included

in the stack. BORING! BORING! BORING! But one day I

found one! I actually found a charge slip that had been inadvertently filed with the cash slips. I don’t remember anyone

else ever finding one. It seemed to make it all worthwhile

somehow.

Sometimes when I came in on a Saturday, I was given the

task of addressing all the statements with a hand-cranked

machine. Names and address of charge customers were stenciled with a ribbonless typewriter on small cards with silkscreen-like centers. The little silk-screens had to be stacked

so they would feed into the machine, along with the statements. Some sort of ink-rolling mechanism picked up the

ink, spread it across the silk-screen and then printed it on

the statement paper as I turned the crank. This was a long,

laborious hand process but faster than typing each statement

individually. It usually took the better part of a Saturday to

do all the addresses. Now a computer would do that in minutes.

I continued to work at Daly Brothers through four years of

college at Humboldt State, every Saturday, every school holiday and every summer vacation, except one summer that I

spent working at Benbow Inn, near Richardson’s Grove. Usually I spent my lunch hour in the lunchroom reading and eating a cheese sandwich and apple that I brought from home to

save money, because I saw too many things I wanted to buy in

the store. Even with my ten percent store discount, less than

four dollars a day didn’t go far.

A 1946 Daly’s newspaper ad encouraged women to purchase hats.

In 1947, a French designer decided women needed a new

look and dropped hemlines to mid-calf. All my short, material-conserving wartime skirts were suddenly out-of-date! For

some strange reason, short skirts actually looked indecent. The

huge sloppy wartime sweaters that revealed six inches of

pleated skirt coming to just above the knees were replaced by

short formfitting sweaters and long straight skirts that were

difficult to walk in, even with short slits up the sides, front, or

back. Dresses had skirts with yards and yards of material.

Brown and white saddle shoes and bobby-sox gave way to

white buck saddle shoes and ankle socks rolled down to show

anklebone.

Even my good wool coat was too short. I cut the coat off to

make a jacket, but it looked like a coat-cut-off-to-make-a-jacket. I was forced by fashion to buy a new-look coat on my

meager earnings, paying for it a little at a time. I did manage

to buy one good long, wool, straight, ankle-length skirt and

two short sweaters.

The new coat was black wool gabardine and cost eighty

dollars. Think how many Saturdays I had to work to pay for

it! Five months of Saturdays, and more. The coat had a scalloped yoke in the front and back, from which flowed princess-style gores that flared out below the waist into a huge

skirt. It wasn’t even a warm coat, but it was in fashion. I’m

not sure if I was allowed to charge it and just turn my pay

envelope back to the store each week, or if I put it on layaway.

I do remember when I finally wore my beautiful new black

coat to work, I hung it carefully on the employees’ coat rack

with dozens of similar coats. When it was time to go home.

my coat was gone. Someone had

taken it, thinking it hers. As I was

fighting tears, the girl who took it

came back into the coat room after

realizing her mistake. What a relief

it was to get that coat back!

When I was starting my junior

year at Humboldt State, the store offered me a full-time job at the fabulous salary of one hundred dollars a

month! I was tempted to take it because I was tired of scraping by with

only two sweaters and one skirt to

my name. But I decided to finish my

education, and in another two years

graduated with a teaching credential

and was able to earn three hundred

dollars a month.

Daly Brothers was very good to

work around my schedule. I had the

opportunity to know some wonderful people. Tillie Atwell was a mother

to everyone-her own large family

and the “store family,” as well as being a very sharp, astute businesswoman and accountant. Gladys

Meline. with her red hair and strict

rules, is a legend in the store. Agnes

did the billing on a huge dinosaur of

a billing machine. I’m sorry I can’t

think of her last name. Francis King

worked in the office during that time.

We discovered that we were cousins

of the same cousin — though we are

not related to each other. I still hear

from her at Christmas. Pat Farrar was

a cashier. I can’t remember the names

of the other cashiers, except one

whose last name was Mackle. Ella

Marie Fanucchi also worked in the

office. I think she was in charge of

the few cash registers scattered

throughout the store in areas that were not convenient to the

tube system. Another girl, whose name was Holly or Polly

something, worked in the office to help her husband pay off a

twenty-five thousand dollar debt on his logging truck. Something had happened to the truck, and he still owed that much

money on it. This was a huge sum, when the minimum wage

was fifty cents an hour, but they both worked hard and paid it

off.

Tillie’s daughter, Anita Atwell, worked in sales. Santina

“Sandy” Del Grande worked in the Center Aisle, Impeccably

dressed, with perfect nails, hair and makeup, and high heels. I

could never understand how she could stand there hour after

hour in heels. Meta Huddleson worked in Lingerie. My older

sister, Pat Roberts, worked in the office before she started her

family and after her boys were old enough to go to school.

My younger sister, Betty Olsen, worked in the Beauty Salon,

after graduating from Beauty College. And my sister-in-law,

Pat Gipson, worked in sportswear.

Although the noise of the “tubes” nearly drove me to distraction at times, I shall always appreciate having had the opportunity to work at Daly’s and make a little extra money while

going to school. The closing of this store is like the closing of

another era — a time gone the way of that Victorian switchboard.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Summer 1996 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.