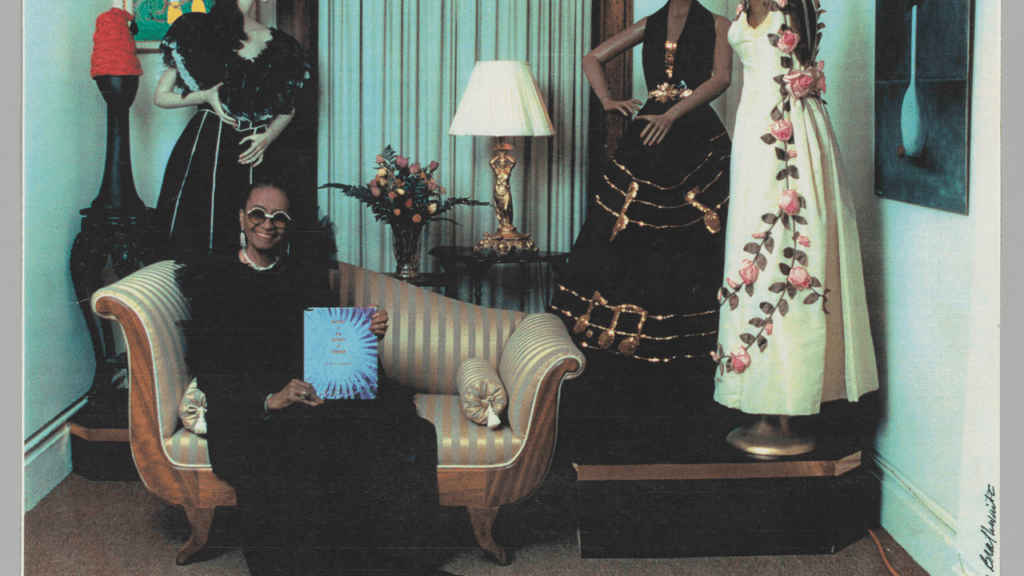

Photographed by Kwame Brathwaite, Lois K. Alexander-Lane is positioned on a golden-striped chaise in a floor-caressing black dress. As her smile widens for the camera, her earrings shimmer as she faces forward, grasping her prolific 1982 textbook, Blacks in the History of Fashion. Capturing her in all her splendor, she is enveloped by her life’s work on all sides as a predecessor of one of the original Black fashion archives.

Born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1916, Alexander-Lane yearned for a life of fashion, daydreaming in department store windows and sketching their designs. After graduating in 1938 from Hampton University, she relocated to Washington, D.C., and worked in the Department of Housing and Urban Development for three decades. Her unyielded love for fashion led her to pursue a master’s degree in retailing, fashion, and merchandising at New York University, titling her thesis, “The Role of the Negro in Retailing in New York City from 1863 to the Present.” In it, she countered limiting beliefs on the Black experience within the New York fashion landscape, referencing Alice A. Casneau’s 1895 book, Casneau’s Guide for Artistic Dress Cutting and Making as a pivotal text in marking the history of tailoring and pattern making by Black designers. While navigating Washington, D.C., and New York, Alexander-Lane opened clothing boutiques in both cities marketed towards the Black bourgeois and their desire for custom clothing.

By 1966, Alexander-Lane founded the Harlem Institute of Fashion to provide a community for people to prepare themselves for jobs in the fashion industry, per the Monterey Herald. Impressively, the designer was also the majority investor in the institution. Students who attended completed two semesters of courses and were able to specialize in dressmaking, millinery, color, and design. In the creation of the H.I.F., Alexander-Lane ushered in a new generation of Black designers with a keen understanding of garment construction. By 1982, the school was credited with graduating over 3,000 students.

The idea to create the Black Fashion Museum originated at the Harlem Institute of Fashion’s Benefit Show in the late ‘70s. At this same time, Alexander-Lane began to draft her grant proposal for the National Endowment of the Arts. Approved in April 1978, the Black Fashion Museum was initially funded by a $20,000 grant, according to Alexander-Lane’s textbook Blacks in the History of Fashion. Since she believed in the vision behind archiving important works, she matched this six-figure amount with her personal funds. This ushered her into a new role as lead curator and project director working alongside consultants, part-time professionals, and volunteers.

Soon after receiving the NEA grant, Alexander-Lane set out on a cross-country tour searching for the roots of Black fashion. She contacted countless newspapers to publicize her search, scouring the nation for familial heirlooms and contemporary clothing. She pushed her press call-out beyond traditional Black publications to receive garments. Because she knew the historical significance of Black seamstresses designing for white patrons in this country she decided to pinpoint this while utilizing the press to her advantage. In a 1981 article for The Washington Post, Alexander-Lane described the museum’s aim to change the image often associated with Black designers. “There is an oft-quoted myth that black people are ‘new-found talent’ in the fashion field and we want to change that,” she said. In Blacks in the History of Fashion, she wrote: “Most of today’s designers tell me they learned to sew from their grandmothers, and that’s who I want to talk to. I want the clothes their grandmothers made.” This is pivotal, as it brings attention to who she was able to gather pieces from over the years–especially since older matriarchs often save pivotal family items and objects of value in their attics.

Launched in a brownstone on 126th Street in Harlem, the Black Fashion Museum acquired 200 garments and accessories for its opening in 1979 and gathered 3,000 pieces prior to its closing. These archival items spanned from muslin dresses and bonnets constructed by enslaved women to a dress sewn by Rosa Parks during the Montgomery Bus Boycotts. On a more extravagant end, the archive also contained a collection of ball gowns and dresses by Ann Lowe, the highly-skilled Black seamstress who produced Jacqueline Kennedy-Onassis’ wedding gown, to a reproduction of Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley’s dress, the formerly enslaved woman who created custom pieces for Mary Todd Lincoln.

Aside from the Black Fashion Museum incorporating contemporary garments within the archive, it took things a step further by also highlighting the work of one of the originators of streetwear, Willi Smith. Smith actively worked with Alexander-Lane to incorporate his collection into the museum’s impressive lineup. Geoffrey Holder’s costumes for The Wiz were displayed alongside dresses from Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf for the BFM’s “Costumes from Black Theater” exhibit. A William Travilla dress worn by Diahann Caroll for the sitcom “Julia” had a home in the archive with Zelda Wynn’s designs worn by both Eartha Kitt and Ella Fitzgerald. Alexander-Lane illustrated the history of Black Americans through the labor we bear in each seam, not shying away from the trauma or limelight that complicates the identities of our textile laborers.

In 1994, the Black Fashion Museum relocated to Washington, D.C. in a historical row house. Alexander-Lane still toiled away with running the institution for years until she began struggling with Alzheimer’s and later in her life liver cancer. By 2007 Alexander-Lane passed at 91. Then the institution was passed down to her daughter, Joyce Bailey, according to The Washington Post. During its last days in the year 2007, the BFM was struggling, The lack of temperature control in the building resulted in garments being damaged due to the humidity. Prior to Alexander-Lane’s passing, priceless artifacts were not in proper storage and instead stored on wire hangers. Funding was also hard to come by. With her passing, her daughter struggled for years to find donations to run the BFM’s archive. Eventually, she was able to donate her mother’s life’s work to the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute. Some of the pieces are housed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Standing in the contemporary moment of fashion, there is a constant negotiation of steps forward and steps back. This creates an illusion of progress at the expense of what is happening in reality. Alexander-Lane knew the importance of having the archive, a special and commemorative holding space for Black garment workers from the few who lived fabulous lives, and the achy-handed women who toiled for hours with needle and thread. It’s exceptional that she saw a need for this and decided to act upon it as a way to pay homage to these designers who are not household names.

Header Image Credit: Black Fashion Museum Archive, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Black Fashion Museum founded by Lois K. Alexander-Lane